The Necropolitics of Radiometric Dating

Radiometric dating keeps revising. The oral traditions it displaced never had to.

The Brief

Examines how radiometric dating assumed authority over Indigenous timelines that already had their own epistemological standing. Through Achille Mbembe's necropolitics, traces how laboratory jurisdiction over deep time determines which histories survive as science and which get reclassified as myth. Case studies: excess argon at Mount St. Helens, Carbon-14 reservoir effects, Rimrock Draw Rockshelter, and the Klah Klahnee oral tradition.

- What is necropolitics and how does it relate to radiometric dating?

- Coined by Achille Mbembe in 2003, necropolitics describes the power to dictate who must die or exist in 'social death.' This article extends the concept to radiometric dating's authority over which historical narratives are validated and which are dismissed as myth, particularly Indigenous oral traditions.

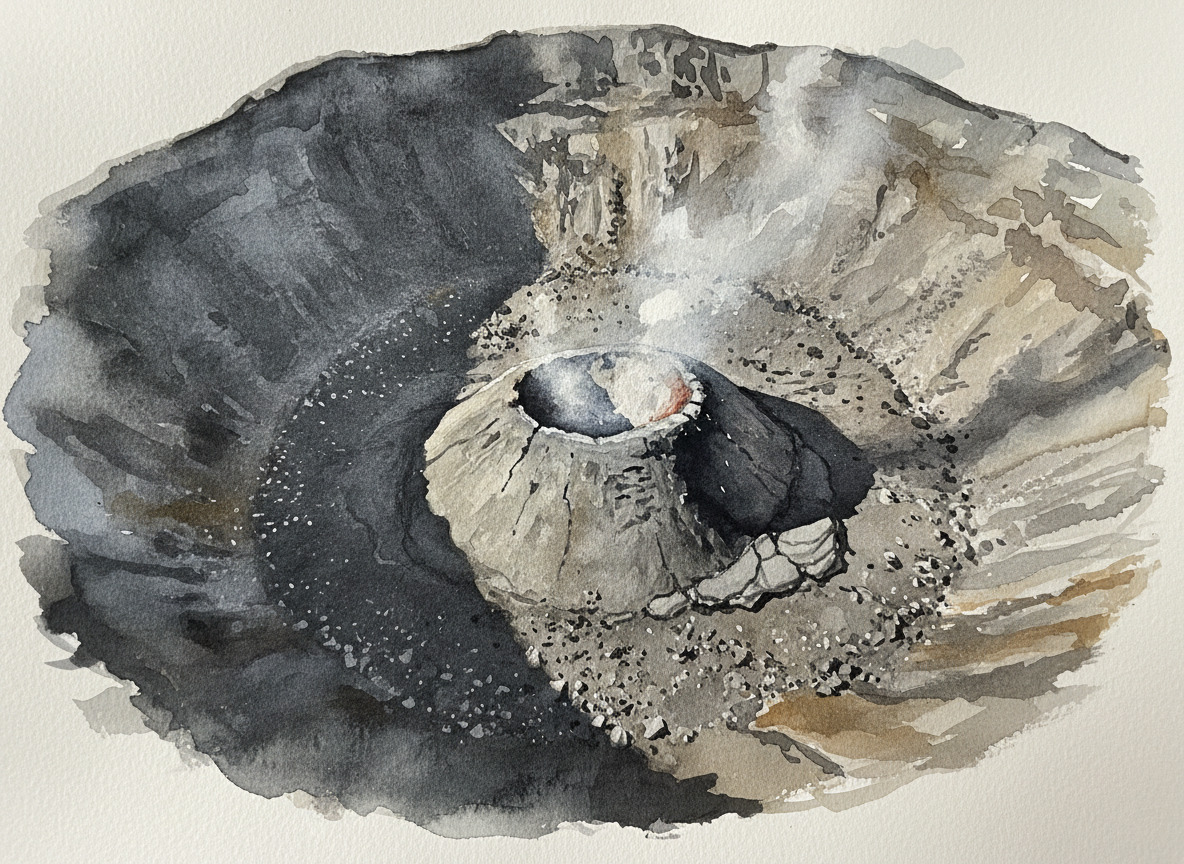

- What went wrong with Potassium-Argon dating at Mount St. Helens?

- Rock formed in the 1986 Mount St. Helens lava dome was dated using K-Ar methods and returned ages between 350,000 and 2.8 million years for material that was only ten years old, due to excess argon trapped in older mineral inclusions within the sample.

- What is the reservoir effect in Carbon-14 dating?

- The reservoir effect occurs when organisms absorb 'old' carbon from ancient water sources, causing them to appear thousands of years older than they are. Living snails in Nevada were dated at 27,000 years old, and freshly killed Antarctic seals at 1,300 years old.

- What is the Klah Klahnee oral tradition?

- Lucy and Walter Miller, Warm Springs Indians, preserved an oral tradition describing a single massive mountain called Klah Klahnee that once stood where Oregon's Three Sisters are today. The mountain was destroyed during a catastrophic volcanic event involving days of earthquakes and falling hot rocks.

- How old is the Rimrock Draw Rockshelter site in Oregon?

- Radiocarbon dating of camel tooth enamel at Rimrock Draw Rockshelter returned a date of 18,250 years before present. The article argues that this date represents the laboratory catching up to what Indigenous oral traditions already held, rather than a discovery of presence that communities never doubted.

I'm taking Biological Anthropology at Oregon State this term, and I can't digest the timeline.

Not the broad strokes. I can hold the idea that humans have been around for a while and that rocks are much older still. What I can't reconcile are the swings. Open a textbook and radiometric dating reads like settled science. Precise half-lives, elegant decay curves, ages landing in neat thousands and millions. But start pulling at actual field results and the numbers stop behaving like science. They start behaving like a stock market. One study dates a sample at 350,000 years. Another lab runs the same rock and gets 2.8 million. The price keeps moving, and the textbook doesn't mention it.

I'm a student trying to make sense of a timeline that keeps revising itself, wondering why the revisions don't seem to bother anyone else in the room.

The Shockwave

May 18, 1980. I was in Salt Lake City when Mount St. Helens erupted. I was young, but I remember the coverage. A mountain 2,500 miles away had just rearranged itself, and the shockwave rippled across the country. It was one of those events that doesn't need a laboratory to confirm it happened. Everyone alive that day knows.

Six years later, a new lava dome formed inside the crater. Fresh rock, born in 1986. When samples from the dome were submitted for Potassium-Argon dating, the results should have come back effectively zero. The rock was ten years old.

Instead, the whole-rock sample dated at 350,000 years. Feldspar crystals came back at 340,000. Amphibole at 900,000. Pyroxene concentrates at 1.7 million and 2.8 million years.1

Ten-year-old rock. Nearly three million years of phantom age.

Fresh rock, born in a decade. Dated in millions.

Fresh rock, born in a decade. Dated in millions.

The standard rebuttal is that the lava dome incorporated older mineral fragments, and those fragments carried inherited argon that inflated the results. I've been sitting with that explanation, trying to work out why it doesn't settle anything for me.

We know the fragments skewed the results because we already knew the rock was ten years old. Eyewitnesses watched it form. The correction depends on having the answer before you run the test. But that's the part that keeps circling back on itself. For the millions of rocks whose age nobody witnessed, how would you detect inherited argon? How would you know which minerals carried old gas and which didn't? You wouldn't. The error is only visible when you already have the answer. And the entire point of radiometric dating is to produce answers you don't already have.

The Carbon Problem

Potassium-Argon isn't alone in the volatility.

In 1984, researcher A.C. Riggs collected living freshwater snails from artesian springs in Nevada and submitted them for Carbon-14 analysis. The snails came back dated at 27,000 years old.2 They were alive when he picked them up.

The culprit is called the reservoir effect. Organisms living in water that flows through ancient limestone absorb carbon already depleted of its C-14. The dating method reads the depleted carbon and assumes the organism is ancient. Freshly killed seals in the Antarctic have returned dates of 1,300 years for the same reason.3 These aren't fringe results. They're published in Science.

Clear water, ancient carbon. The springs don't look 27,000 years old.

Clear water, ancient carbon. The springs don't look 27,000 years old.

The reservoir effect is an aquatic phenomenon. You won't find it in a deer bone from a forest. But there's a deeper principle underneath it that I keep coming back to. Carbon-14 doesn't date the organism. It dates the carbon the organism absorbed during its lifetime. A snail and a land animal standing next to the same spring, alive at the same moment, would produce wildly different dates. Not because they lived in different centuries, but because they breathed in different carbon.

That distinction matters more than it might seem. Every C-14 date carries a buried assumption: that we know where the sample got its carbon and that the carbon behaved the way we expect. For the snails, we caught the problem because we know the springs flow through ancient limestone. For a bone fragment pulled from a 10,000-year-old stratum, we're trusting that the carbon environment was what we think it was. There's no eyewitness for that.

And that circles back to the same structure as the argon. The method works until it doesn't. And when it doesn't, you only find out if you had some other way of knowing the answer first.

Entering the Realm of Necropolitics

I came across the word "necropolitics" while reading for another course. Achille Mbembe coined it in 2003, extending Foucault's concept of biopower. Where Foucault described how governments manage populations by controlling who thrives, Mbembe went further. Necropolitics is the power to dictate who must die. Or more precisely, whose existence gets relegated to what he called "social death." Alive, but rendered invisible by the systems that govern meaning.4

I kept thinking about that phrase after class. I've been reading about dating methods this week, and something clicked. Because necropolitics describes exactly what happens when the laboratory claims jurisdiction over histories that already had their own standing. Indigenous oral traditions weren't waiting for a number to confirm them. They were complete accounts, carried by communities across generations, with their own logic and their own evidence. The laboratory didn't argue with those accounts. It simply replaced them. The method became the authority. If a history didn't match the numbers, it got reclassified as myth. Not disproven. Just dead on arrival.

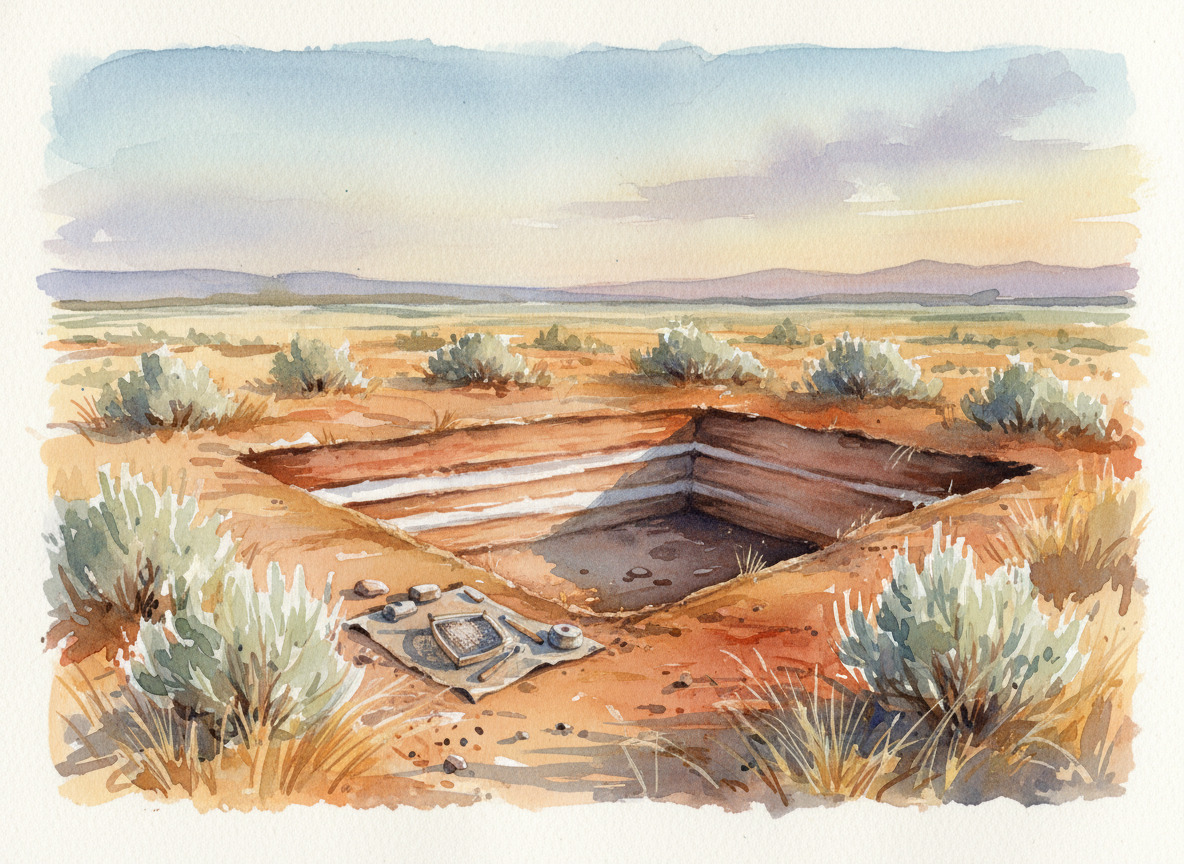

Rimrock Draw

Consider Rimrock Draw Rockshelter in southeast Oregon. Archaeologist Patrick O'Grady's team found an orange agate tool beneath a layer of Mount St. Helens ash dated to roughly 15,600 years ago. Radiocarbon analysis of camel tooth enamel from the same stratum returned a date of 18,250 years before present.5

That number matters, but not for the reason the headlines suggest. The press coverage frames it as a breakthrough: human presence in Oregon pushed past the Clovis barrier, the long-held model that people first arrived in the Americas about 13,000 years ago. And it is significant. But the communities whose ancestors made that orange agate tool didn't need a camel tooth to know they were here. Their oral traditions never placed a start date on their presence. They were already here. That was never in question, except inside the laboratory.

The Clovis model was a laboratory construction. It drew a line at 13,000 years and told an entire hemisphere of people that their history began on the other side of it. When Rimrock Draw pushed the date back to 18,250, the gate moved. But the people on the other side of it hadn't moved at all. They'd been telling the same story the whole time.

Digging for evidence of something that was never in doubt.

Digging for evidence of something that was never in doubt.

What stays with me is the direction of revision. Oral traditions didn't update when the Clovis barrier fell. They didn't need to. The traditions were never wrong. It was the laboratory's model that kept revising. And somehow the thing that keeps revising retains authority over the thing that held steady.

The Three Sisters

This is where it gets personal.

Lucy and Walter Miller were Warm Springs Indians who carried a story from their childhood, passed down through their families. They remembered a time when the largest mountain of all stood where Oregon's Three Sisters are today. They called it Klah Klahnee. The earth shook for days, they said, and red-hot rocks rained from the sky. Where one mountain had stood, three remained.6

The Millers remembered one mountain. The laboratory insists there were always three.

The Millers remembered one mountain. The laboratory insists there were always three.

Geology tells a different story. According to the USGS, North Sister last erupted around 55,000 years ago, Middle Sister between 40,000 and 14,000 years ago, and South Sister between 50,000 and 2,000 years ago.7 Three separate volcanoes, formed across tens of thousands of years. Not a single mountain that broke apart.

But here's where I stall. And I want to be honest about why, because the easy version of this argument has a hole in it. Geology doesn't rest on dates alone. The Three Sisters are physically separate vents with different compositions. You can look at the rock and see that they're distinct structures. That's not a number on a printout. That's observation.

But the Millers weren't describing a quiet divergence over millennia. They described a catastrophe. Days of earthquakes. Red-hot rocks falling from the sky. And catastrophic volcanic events reshape landscapes in ways that uniformitarian geology, the assumption that processes happen gradually, can struggle to reconstruct after the fact. A mountain that collapses during days of seismic violence doesn't leave behind a tidy record of its former shape. It leaves behind whatever survived the event.

Both the geologist and the Millers are interpreting the same mountains. The geologist reads the current landscape and works backward, assuming gradual processes. The Millers carried an account from people who watched it happen. One interpretation gets published in USGS reports. The other gets cataloged as legend.

That's necropolitics applied to deep time. Not a conspiracy. Not deliberately bad science. But the laboratory's reading of the physical landscape gets treated as observation while the Millers' tradition gets treated as mythology. A living memory, carried by real people across real generations, filed alongside folklore. Nobody asked whether that filing system made sense.

A Fresh Timeline

I don't have a replacement theory. I'm an anthropology student, not a geologist. But I have questions my coursework hasn't answered, and the numbers aren't helping.

When Potassium-Argon gives you 2.8 million years for rock you watched form a decade ago, and Carbon-14 gives you 27,000 years for a snail you could hold in your hand, you're not looking at a stable foundation. You're looking at a market in correction.

The textbook revises. The mountains don't.

The textbook revises. The mountains don't.

But the volatility isn't the main point. Oral traditions don't deserve attention because the instruments failed. They deserve attention because they had standing before the instruments arrived. Communities carried accounts of their own history, tested across generations of living memory, long before a laboratory claimed jurisdiction over the timeline. The instruments didn't earn that authority. They just arrived with more institutional weight behind them.

The failures I've been describing don't make the case for oral tradition. Oral tradition already had its case. The failures just make it harder to ignore. A field that keeps revising its own answers claimed the right to dismiss accounts that never needed revision. That's worth questioning.

The Millers remembered Klah Klahnee. The laboratory says it never existed. I'm not sure the laboratory has earned the final word.

References

Footnotes

-

Excess argon in young volcanic rocks is a well-documented phenomenon in geochronology. K-Ar analysis of the 1986 Mt. St. Helens lava dome returned ages between 350,000 and 2.8 million years for ten-year-old rock. For foundational research, see Dalrymple, G.B. (1969). "40Ar/36Ar analyses of historic lava flows." Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 6, 47-55. For a comprehensive review, see Kelley, S. (2002). "Excess argon in K-Ar and Ar-Ar geochronology." Chemical Geology, 188(1-2), 1-22. ↩

-

Riggs, A.C. (1984). "Major Carbon-14 Deficiency in Modern Snail Shells from Southern Nevada Springs." Science, 224(4644), 58-61. ↩

-

Keith, M.L. & Anderson, G.M. (1963). "Radiocarbon Dating: Fictitious Results with Mollusk Shells." Science, 141(3581), 634-637. ↩

-

Mbembe, A. (2003). "Necropolitics." Public Culture, 15(1), 11-40. Summary at Critical Legal Thinking ↩

-

Bureau of Land Management (2012). "Testing Yields New Evidence of Human Occupation 18,000 Years Ago in Oregon." BLM Press Release ↩

-

Clark, Ella E. (1953). Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. University of California Press. Oral tradition of Lucy and Walter Miller, Warm Springs Indians. ↩

-

USGS. "Three Sisters Geology Summary." USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory ↩

More to Explore

Your AI Has Amnesia

You wrote the rules. Your AI followed them. Then it quietly stopped.

The Pilot Graveyard

AI tuberculosis detection worked beautifully in Kenya. Then the grant ran out and nobody could pay for the subscription.

Your Page's Resume

You let the crawlers in. What they found looks nothing like your website.

Browse the Archive

Explore all articles by date, filter by category, or search for specific topics.

Open Field Journal